How Braille Literacy is an Important Step Towards Social Inclusion

Social inclusion can seem a pretty straightforward idea - everyone is entitled to, and must hence be enabled to fully participate in society. But ensuring that socially disadvantaged people, such as those with visual impairment, are actually empowered and included in society is far from straightforward. This process begins from childhood, with enabling access to opportunities to develop visually impaired children’s individual and social skills. But where many well-intentioned efforts at such inclusion goes wrong is in assuming that it is sufficient to simply bring disadvantaged people into settings built for the able-bodied. The classroom as we know it, for example, is not suited to the needs of a visually impaired child.

Initiatives that place the burden of inclusion largely on the person with disability, however, are limiting. The social inclusion of visually impaired children shouldn't be the sole responsibility of the children themselves but should be encouraged by their families, their peers, their friends and their educators. As many scholars and educators working with visually impaired children and adults argue, we need to move from a purely medical view of disability, to a social view, which understands the social barriers to a visually impaired person living a full life on their terms. To remove these barriers, then, requires us to empower the visually impaired person from their childhood to live their own individual lives, while establishing robust support systems and environments. A comprehensive education is evidently a key aspect of such a life. And for visually impaired children in particular, Braille learning is an important part of inclusive education, and so of true social inclusion - the ability to navigate the world on their own terms with the support of their social environments.

Inclusion begins with all of us

Melinda Jones, a disability advocate and human rights scholar, writes that inclusion is “is the right of the individual and the responsibility of society as a whole,” requiring that we all acknowledge disability rather than overlook it, as a means to make societal participation possible. She identifies three key dimensions of inclusion: “a non-discriminatory attitude towards people with disabilities; the guarantee of access to participation in every area of life; and the facilitation of people with disabilities to limit the impact of disability.”

Inclusive education in particular advocates for bringing disadvantaged children - such as those with visual impairments - into classrooms in which generally only sighted children learn. The idea with this is to foster a sense of equality amongst the children, and a holistic view of the child’s development, where visually impaired children learn from the same resources and curriculum typically afforded only to sighted children. The classroom and its learning processes must be adapted to allow the visually impaired child opportunities for meaningful participation and interaction with their teachers and classmates.

Friendships are among the most important social elements of a disabled child’s school life, and inclusive education cannot succeed with an educational setting that encourages and enables a sense of classroom community and friendships within a diverse group of children. Such interactions can be encouraged by teachers too, through themselves having positive and inclusive interactions with students with disabilities and adapting their teaching methods and materials to these students’ needs. Teachers must recognize, however, that having students with disabilities in their classroom will affect regular teaching processes, requiring them to invest more time and undertake additional responsibilities in addressing the disabled child’s specific needs.'

Social and classroom inclusion can also be enabled through technological means, such as ensuring that learning materials and tools are compliant with accessibility standards from the start, following a user-centered design process for developing materials in disabled-friendly formats such as Braille and audio, and incorporating built design into physical classrooms. Inclusive technological use isn’t limited by what persons with disabilities want to use, but what choices they’re provided with - often as an afterthought to the development of technology for able-bodied users.

Visual impairment and Educational Inclusion

For children with visual impairment, inclusion in the classroom and at school is twofold: teaching from a curriculum specifically tailored to their needs, as well as encouraging the development of life skills, mobility and tactile awareness of the world around them with their friends and teachers. But with inclusive educators often choosing to prioritize the academics over the social development of children, the latter suffers. This isn’t necessarily deliberate - it’s an oversight that can be remedied with consistent efforts and a close understanding of the lives of visually impaired children.

When teachers work with visually impaired children, they could facilitate curriculum delivery via non-visual means alongside a visually-based presentation that can be made accessible. It’s also important to adopt participatory teaching methods so the visually impaired child can interact with the teacher and their peers without relying on visual modes of communication. The classroom must also have technical modifications that support both the teacher and the student, such as computers with multimodal speech and tactile software, screen magnifiers and/or readers, and means of orienting themselves in the classroom, often with their friends’ help.

Technology that enables inclusivity should be designed to be both accessible and responsive to the specific needs of the visually impaired child. Per education researchers Alan Foley and Beth A. Ferri, such technology would “offer the opportunity to ‘re-crip’ technology by honouring and valuing interdependence and different, disability-specific ways of being in the world,” while aiming to enhance the ‘cool’ factor that would encourage the use of useful technology, especially among young learners. They note “that if technology is to reduce social isolation, it must be designed with social inclusion in mind.”

Inclusive education interventions need to happen on an administrative level, a classroom level, and an individual level. A deep understanding of the visually impaired students’ social and emotional needs is required, supported by the social and material environment providing both tools and contexts to make real social inclusion possible. A close and strong relationship between the educator and the student actually facilitates the child’s independence, as this inclusion improves their self-confidence, self-esteem and self-acceptance as valued participants in the classroom. This is especially helpful in the visually impaired child’s transition to adolescence, and the increased socialization that comes with it. Visually impaired students supported with the common curriculum by their sighted classmates improves their socialization and academic performance immeasurably.

Braille as a Means to Social Inclusion

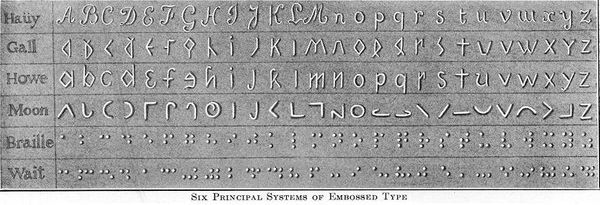

Braille learning has been an important part of visually impaired children’s education for centuries. In the modern inclusive classroom, Braille is key to a visually impaired child’s reading and writing skills, enabling them to master the rules of spelling, punctuation, grammar in a script created for them to access text, mathematics, music, and other information. The combination of traditional learning and Braille technology is an important step forward in helping young Braille learners not only to master the tactile literacy medium but also experience high-end technology features they are very likely to continue to use as they advance through their education.

Educators therefore need to create optimum environments to promote the development of literacy through Braille whilst considering the child’s needs for social inclusion. This requires ‘immersing’ pupils in Braille, to integrate listening, speaking, reading and writing, to work with a strong focus on meaning by describing the world and providing time to explore real objects, using the visually impaired child’s interests and progressively bringing new experiences. Braille and associated auditory comprehension tasks can also help with the development of ‘memory skills and tactile tactics in order to compensate for the sight absence.’ The benefits of Braille also make it evident that technological devices should be used to enhance Braille learning and use, not to replace it. Given that it provides a holistic means of text comprehension, Braille functionality must be taken into account in the design of technological and digital learning systems.

Early support to children for learning Braille through a system of comprehensive language teaching is key to their education, cultivating the proficiency necessary to freely use the script as a tool for contact with human thought, i.e. reading and writing comprehension. Furthermore, language is crucial for children with visual impairment as it plays a major role in establishing social and environmental contact. Braille is the only dual reading and writing system for personal use, offering privacy that audio devices do not offer, particularly in some public spaces. There is also a range of evidence to support the early and extensive acquisition of Braille having clear benefits for increasing employability, independence, confidence, and self-determination for people with visual impairments - their literacy enables, by extension, their expressiveness. Our own innovation in Braille learning, Annie, folds in such wisdom to create a space for comprehensive multimodal education in a classroom setting.

Making Inclusion Happen

The truth remains, however, that much of the social and political power in our world rests with sighted people. The onus for making education inclusive, and hence pave the way for social inclusion of those with visual impairments, remains with them. At broader organizational levels, schools, governments and parents need to collaborate with the express purpose of laying the foundations of an adequate and effective inclusion of visually impaired children.

Thankfully, this path to inclusion too, can begin in the classroom. When sighted children regularly engage with their visually impaired peers, they gain empathy for the consequences of disability. When Braille is incorporated in the classroom alongside traditional language scripts, it sparks a curiosity in sighted children that leads to camaraderie with visually impaired children. Jolene Wallace, a veteran teacher of the visually impaired notes that this “provides a way to identify and address misconceptions that sighted students may have about vision impairments. For the vision impaired student in the class, it can offer a chance to take a leadership role, practice social skills, and answer questions that classmates may have about him or her in a safe and comfortable environment…[shaping] a shared mode of literacy.”

Our objective with inclusive education through social, technological and environmental initiatives in Braille and more must be, then, to shape their place in the world. All of us play a role in such a journey. After all, only an inclusive society can be a just society.